Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Imagine a gymnast performing a routine on the floor. Their movement options are almost endless: they can run, flip, cartwheel, jump or spin.

However, any movement they perform can be divided into three broad categories of movement, which anatomists describe using the three planes of movement: They can move forward or backward, crawl or turn left or right. (Of course, you can also combine any of these movement types, but we’ll talk about that later.)

Understanding how your body moves within these planes will give you another tool that can help you make your training safer, more effective, and more fun.

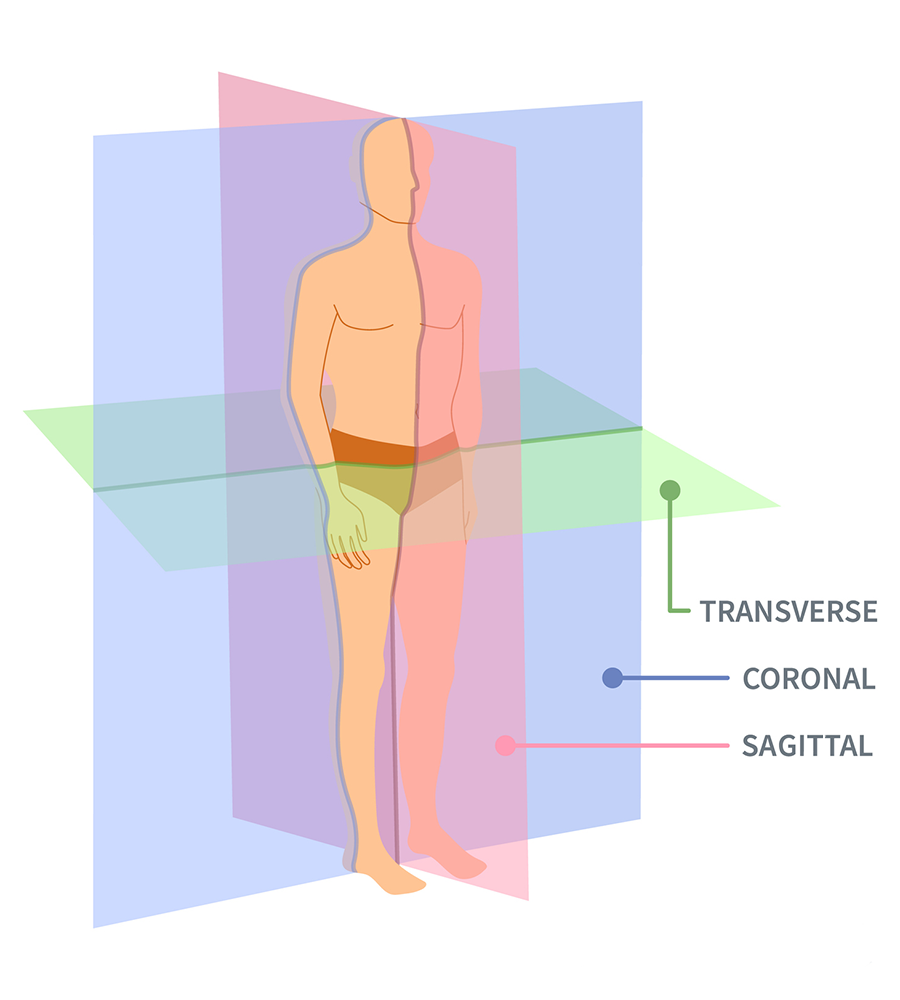

Planes of motion are a way to describe and understand human movement of all kinds, from exercising to dancing to breathing, through a more precise anatomical lens. You can think of these planes as sheets of glass that divide the body into different halves:

Any movement you perform that is broadly parallel to any of those body planes is considered to occur in that plane of movement.

Confused? Stay with us.

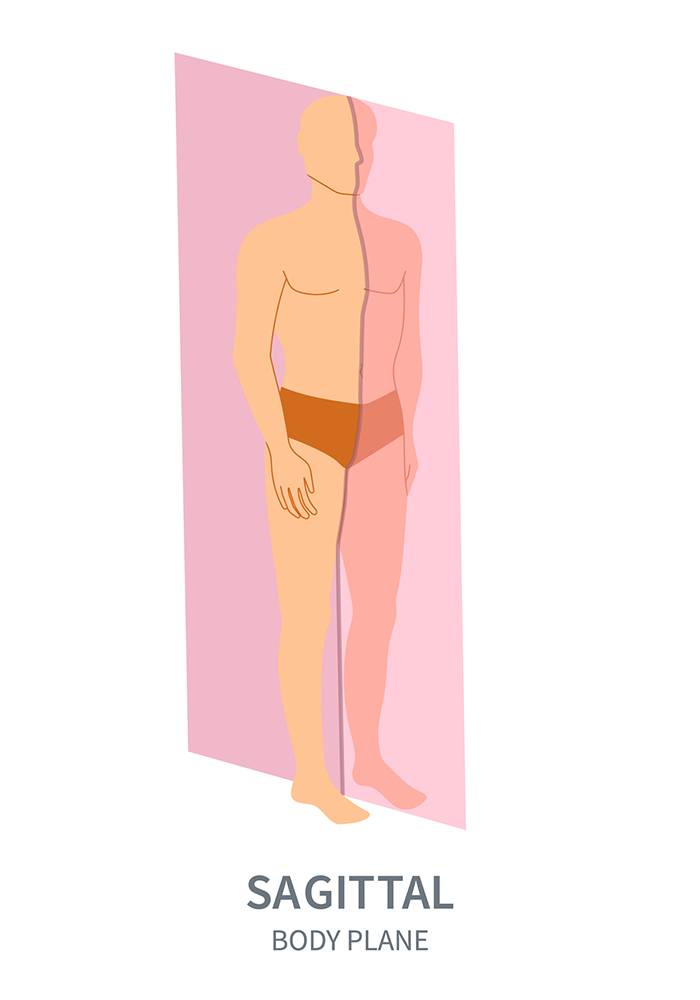

The plane that we encounter most frequently in life (and probably the easiest to understand) is the sagittal, either longitudinal plane. This is the plane that cuts you in half vertically at your center line, separating the left and right sides of your body.

Any movement in which the limbs or spine move along this line, or parallel to it, is considered sagittal or longitudinal. (sagittal It comes from a Latin word that means “archer.”.“Imagine shooting an arrow from a bow at a distant target and you’ll get the idea.)

Movements in the sagittal plane:

Many classic gym moves are considered sagittal plane dominant: lunges, squats, chinese, absabs and Lizards. In these exercises, the arms, legs or spine move parallel to that central sagittal plane. (The forward and backward jumps are also sagittal.)

Everyday movements like walking, where the arms and legs swing back and forth, are also mostly sagittal. It is the plane on which most of us feel most comfortable.

From a therapeutic or anatomical perspective, flexion and extension (curving the spine forward or leaning backward) are classic examples of sagittal movement.

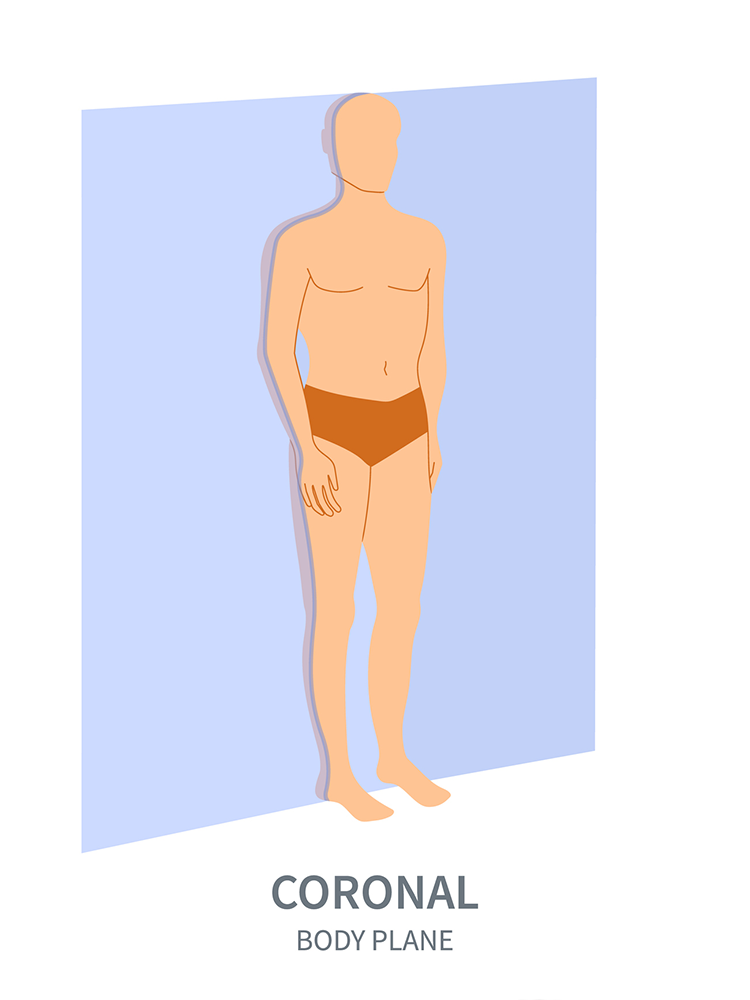

More difficult to imagine but equally important is the frontal either coronal plane. This is the plane that runs vertically through the body, from one side to the other, and separates the front and back of the body.

Imagine standing on a narrow ledge with the entire back of your body (heels, calves, buttocks, upper back, elbows, the back of your hands, and the back of your head) pressed against a wall. Any movement you can make while maintaining those points of contact is a movement in the frontal plane.

Movements in the frontal plane:

Frontal plane movements include dodgeeither shuffle laterallyspreading your arms on the sidestilting the head to the left and right, or lateral flexion your entire torso in one way or another. If you are agile and brave, cartwheels also occur in the frontal plane.

Lateral movements in sports like basketball and tennis are all frontal. side lunge It is also a frontal movement.

Anatomically, abduction (or raising the arm or leg away from the center line) is a movement in the frontal plane.

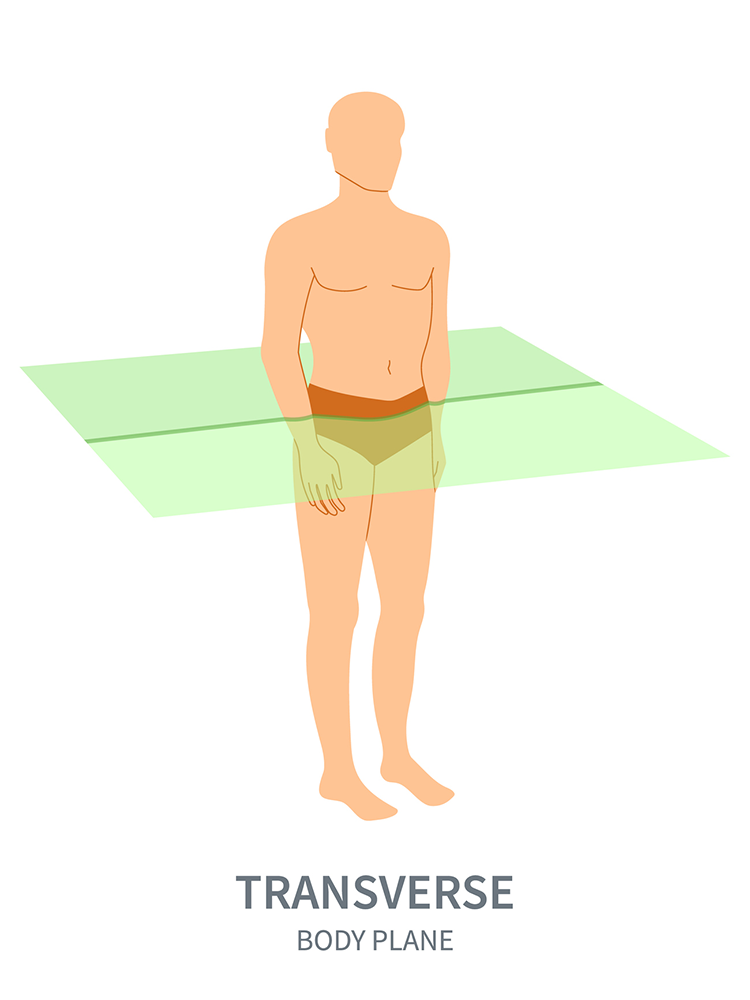

We don’t think much about the final plane of motion, even though we move through it all the time. It is the plane that runs parallel to the ground, also known as transverse either axial plane.

This plane encompasses rotation around its vertical axis. A ballet dancer’s pirouette is a classic example: her entire body rotates around a single, still point.

Movements in the transverse plane:

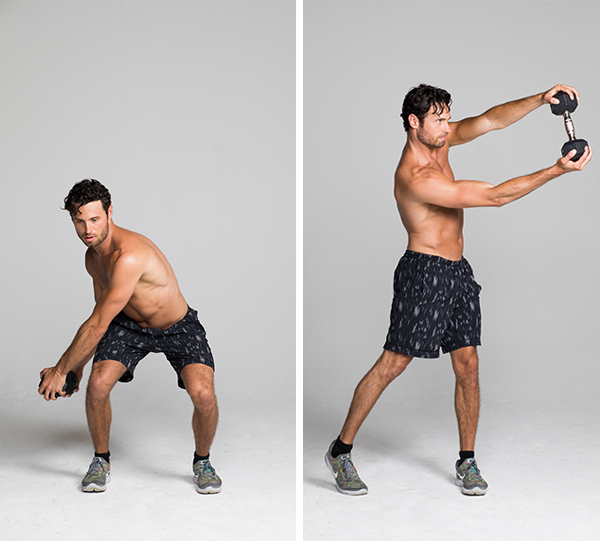

We often see movement in the transverse plane in warm-ups — Hip circles, neck rolls, ankle circles, and trunk rotations are good examples. Some core movements, such as russian twists either bicycle abs – are dominant in the transverse plane, as are many of the rotating stretches in yoga.

Many of the most powerful athletic movements you can do, such as swinging a bat or racquet, throwing a puck, or executing a roundhouse kick or hook punch in MMA, are transverse plane movements; If you want to generate energy, the transverse plane is your ticket.

Anatomically, rotating any joint along an axis is a movement in the transverse plane.

Jargon Alert: The following terms, typically used in medical or therapeutic settings, describe various locations, directions, and types of movement in the body. In all cases, assume you are referring to a person standing with palms turned forward and thumbs pointing outward:

| Former | Towards the front of the body |

| Later | Towards the back of the body |

| Deep | Farther from the surface of the body. |

| Superficial | Closer to the surface of the body. |

| distal | Farther from the center of the body or the origin of a body part (i.e., the ankle is distal to the knee, while the toe is distal to the ankle). |

| proximal | Closer to the center of the body or the origin of a body part (i.e., the shoulder is proximal to the elbow, while the elbow is proximal to the wrist). |

| Lower | towards the feet |

| Superior | towards the head |

| Side | Far from the center line of the body. |

| Half | Towards the center line of the body. |

| Median | The midline of the body. |

| Kidnapping | The movement of a limb away from the center line of the body (i.e., while standing, raising the arm to the side) |

| Adduction | The movement of a limb toward the centerline of the body (i.e., from standing, lowering the arm from a position above the head to the waist). |

| Eversion | Lateral movement of the feet (that is, towards their outer edges) |

| investment | The medial movement of the feet (that is, towards their inner edges) |

| Extension | The opening or straightening of a joint (i.e., straightening the arm at the elbow) |

| Flexion | Flexing or closing a joint (i.e. bending the knee) |

| External rotation | The turning of a limb away from the centerline of the body (i.e., while standing, rotating the leg at the hip joint so that the foot rotates outward) |

| Internal rotation | The turning of a limb toward the centerline of the body (i.e., while standing, rotating the leg at the hip joint so that the foot turns inward) |

| Pronation | The turning of a hand or foot medially or toward the center line (i.e., turning the hands palm down or putting weight on the inside of the foot). |

| Supination | Turning one hand or foot to the side or away from the center line (i.e., turning the hands palms down or putting weight on the outside of the foot). |

When designing a training program for yourself, especially if your goals include athletic performance, pain reduction, and longevity, it is beneficial to consider the planes of motion in which your exercises occur, not just the muscles you are training.

By now you know that most gym moves (and training programs) are sagittally dominant (just walk through the cardio area of any gym and the proof is there). This is not bad: run, climb stairssquat, lunge and cycling They are all great exercises.

But these sagittal movements do not fully stimulate the stabilizing muscles, particularly in the lower body. Over time, this can lead to injuries. Therefore, you’ll likely extend your lifespan in the fitness trenches by also including some frontal and transverse plane movements in each workout.

Training programs at BODi are all designed to move you through all three planes of motion while emphasizing compound exercises (multi-joint)helping you feel fit and strong in everyday life.

The plane of motion model is not exact; No human movement occurs exclusively in a single plane of movement, and one could probably object to the categorization of almost any movement.

A Overhead Grip Pull-UpsFor example, it could be described as a sagittal movement because the elbows move forward in relation to the trunk. But if the elbows tend to move outward instead of forward, that makes it more of a frontal plane movement.

Our bodies are not made up of right angles, straight lines, or hard edges. Every time you take a step forward or backward (a sagittal-dominant movement), the joints in your knees, ankles, and hips also subtly move in the frontal and transverse planes to absorb the forces traveling through the skeleton. Every movement you make occurs on all three planes.

The answer to this dilemma? Don’t worry about that. The planes of movement are approximate.